Serialization and Schemas in Ossium

Hello! Today I’m going to chat about a paradigm used in data-driven game engine design: the type schema. I’m currently working on Ossium, a small 2D game engine; it’s a pretty self-contained game engine, providing an interface for managing disparate systems and game object data. One of the key features in Ossium is a serialization system that allows me to convert a game object (or even a bog standard class) into a JSON string. This forms the foundation for data-driven game design in the engine, as it will allow me to tweak property values of game objects without touching the code to some degree, which is great for rapid prototyping and general game development.

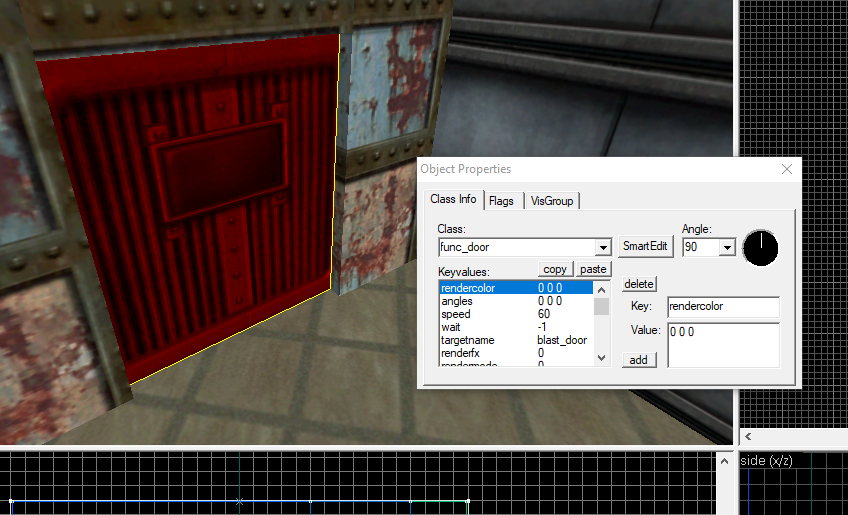

The JSON format is great, as it represents data in key-value pairs which is how almost all game engines represent data. For instance, Valve’s Hammer Editor represents the properties of entities as simple key-value fields.

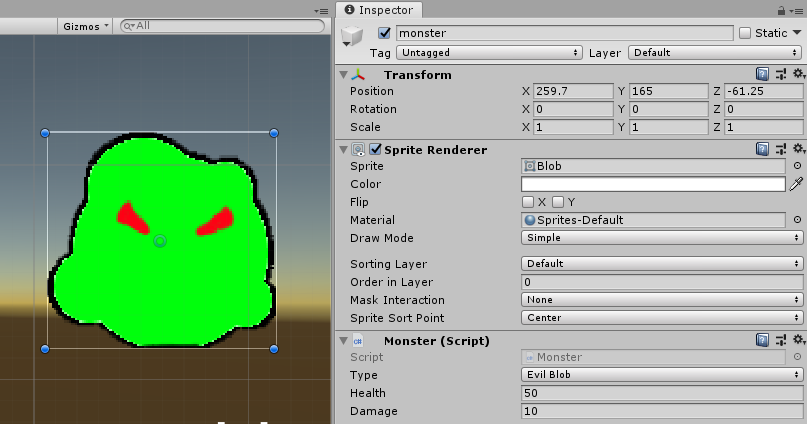

The serialization system in the Unity engine uses a similar representation, with public members of objects displayed in a key-value format where the member name is the key, and the data field shows the member’s value.

Design like this is practically universal in engines where not all data is hardcoded into the game, perhaps with the exception of small, primitive engines that rely on purely sequential formats (such as raw binary) to store information about game objects outside of the runtime environment.

Of course, how these key-value fields are defined varies greatly between engines, and sometimes there is a huge

difference between the runtime representation and the external, persistent data representation. Some engines

use variants to bridge this gap, which effectively abstracts the type of a variable such that the variable could be a string,

a number, a boolean - whatever - and this type is not resolved until the variant is actually used.

This is powerful if one wants to dynamically add or remove properties from a game object, without necessarily modifying

code directly. However, while this is very useful during development, in many cases field definitions are not created

or removed at game runtime. This makes variants somewhat unnecessary for most entities. Variants also add more

complexity and overhead to the code, especially in a language that does not inherently support complex variants such as C++

(instead you must use an implementation like std::variant, which often requires a lot of boiler-plate code to use).

Some engines use what is known as a schema to define the key-value properties outside of the runtime environment. A schema basically defines the property fields of an object, much like members of a class, but might be defined outside of the runtime environment. These schemas are then used to determine how properties are represented in, say, an editor, e.g. showing a dropdown list for enumerated data types, or perhaps a colour picker for setting custom colour values. The schema properties can then be implemented at runtime using variants. This allows game designers to create a schema which specifies the properties of an entity, without a programmer creating a whole new class. Some engines support a high-level scripting language, so a game designer can even program entities themselves. In fact, a game engine may even determine the behaviours of an entity by itself without ANY additional scripting. For instance, if a designer creates a schema that has a health property, the engine could automagically apply logic to the entity, such as reducing the entity’s health when it gets hit and destroying the entity when it’s health runs out. This would let a designer churn out a whole bunch of different monsters or enemies pretty easily.

Ossium’s schema system is very simple as it doesn’t support a high-level scripting language or deterministic behaviour

based on properties. In fact, it doesn’t even use variants. The system works in a similar manner to the Unity and Unreal

engines, in the sense that all the properties are defined as members of a class within the code itself.

Due to the lack of reflection in C++ (for now!),

there is some boiler-plate code required to make the class serializable, much like the Unreal engine. However, unlike Unreal,

there is NO externally generated code - everything is done with classes and macros so you can just hit compile and things

should work out of the box, provided you’re using a compiler with std=c++17 enabled.

How to use the Schema system in Ossium

To create a schema in Ossium, you must declare a class or struct that inherits from the Schema template. For example,

let’s say we’re making a Monster class:

struct MonsterSchema : public Schema<MonsterSchema>

{

DECLARE_SCHEMA(MonsterSchema, Schema<MonsterSchema>);

M(int, health) = 50;

M(int, damage) = 10;

M(vector<string>, inventory);

};

class Monster : public MonsterSchema

{

public:

CONSTRUCT_SCHEMA(SchemaRoot, MonsterSchema);

// ...

};

The struct MonsterSchema is our actual schema. It inherits from the Schema template class, with it’s own type

passed in as the type argument; the Schema template class defines a whole bunch of methods and static storage for

meta data about the members, such as their names. Within the struct itself, we must use the DECLARE_SCHEMA() macro,

passing in the schema type and the inherited type. This macro declares some additional meta data unique to the schema type.

The members of the schema must be wrapped in the M() macro if you wish for those members to be serializable,

with the member’s type first, followed by it’s name. The basic functionality is identical to declaring a member variable,

so you can assign a default value; in addition to declaring the variable however, the macro declares a unique static

object that is used to setup string conversion of the member’s data, with correct type casting. As long as the member type

is supported by a ToString() and FromString() function, you can use any type. At present Ossium supports basic data types

and some standard data types such as std::vector out of the box; if a type isn’t supported, the code will still compile but

you will not be able to serialise the member unless you implement a ToString() and FromString() function or method

for that specific type.

Finally, we create a separate class for the implementation of our actual Monster where we can have any members we don’t

want to serialise with the schema. It inherits from MonsterSchema and uses the CONSTRUCT_SCHEMA() macro, which declares

a whole bunch of methods for accessing and serialising members from the class and the base schema class. In this case,

the Monster class doesn’t inherit from any other classes that implement a schema, so we pass the SchemaRoot type which

acts as a placeholder as the first argument, followed by the type of schema we are implementing (in this case MonsterSchema). That’s it!

But what if I want to make a class with it’s own schema that inherits from Monster!? I hear you cry!

Never fear! The process is the same. For example, let’s say we make a special class called Blob that

inherits from Monster and implements a schema called BlobSchema:

struct BlobSchema : public Schema<BlobSchema>

{

DECLARE_SCHEMA(BlobSchema, Schema<BlobSchema>);

M(float, blobbiness) = 1.0f;

M(string, name) = "Mr Blob";

};

class Blob : public Monster, public BlobSchema

{

public:

CONSTRUCT_SCHEMA(Monster, BlobSchema);

// ...

};

This time, because we inherit from Monster which implements it’s own schema, we pass the Monster type as the first

argument in the CONSTRUCT_SCHEMA(), followed by the schema we just inherited from which is BlobSchema in this case.

Now we have a Blob class that can be serialized including the schema we inherited via Monster. Ta-da!

I hope you found this article interesting! If you want to learn more about Ossium, you can delve into the code on github.